Welcome to the first in a series of blog posts that is dedicated to analysing and utilising a particular lick, phrase or sequence by a range of different instrumentalists and composers. Although all examples will be provided in notation and guitar tablature, this is not guitar specific. It will not be focused on what particular guitar techniques are used or any other practical explanation; rather, what scales and modes are used over given chords and how to assimilate these ideas into your own playing. Different melodic, harmonic and rhythmic devices used in a particular passage will be isolated and conceptualised in a comprehensible way that is easy to understand and digest. I will be going further than merely providing you with an analysis, giving you a step-by-step method of how to effectively break down these ideas and come up with your own. Similarly, the focus won’t be solely on guitar players. I am a firm believer in transcribing and learning from instrumentalists outside of your own discipline, and so this series will see some rigorous analysis of music by Tim Miller, Claude Debussy, Cannonball Adderley and this weeks focus: the formidable Allan Holdsworth.

To many, the music of Allan Holdsworth is utterly enigmatic (unfamiliar? check THIS out). Some people come away confused, disorientated and downright offended. If you are like me, however, you came away enthralled and above all: curious. Over a period of years this curiosity flourished into complete obsession; his byzantine improvisations and cerebral harmonic palette stimulating both my emotions and my intellect. I recall the same sense of wonder upon first hearing Jimi Hendrix’s guitar solo on ‘Highway Chile’ almost a decade prior; his raucous lyricism leaving me with the same breathless yet burgeoning fascination: how did he create that sound?!

Holdsworth’s uniqueness stems from the fact that he created his own system of understanding music. He professes to be wholly ignorant of the established theory of music born from the western classical tradition, and even the conventional chord-scale method adhered to by the vast majority of improvisers from the mid 20th century onward. In an interview with Steve Adelson, he states: ‘To me, it’s a really logical system. I recognize and see certain scales; I don’t think about what the root is. I just see a permutation of intervals. When I look at the neck the notes just light up where those scales would be. I hear a chord or a color, the harmony is one color and you can get two or three things that come along on top of it that match it.’ Whilst his system is a chord-scale system, he has his own names and symbols relating to particular scales, modes and chords. Of course, we can make sense of his improvisations using traditional chord scale analysis, and each one of his scales has its counterpart in our system.

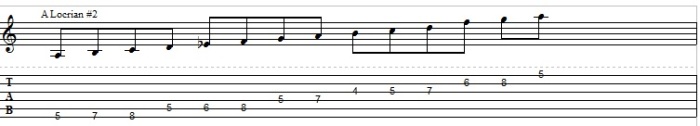

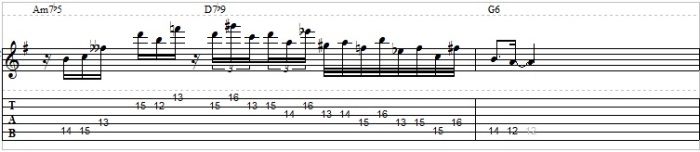

Lick One: ‘Nuages’

Django Reinhardt composed this piece and recorded it numerous times in the 1940s, and it has since become a jazz standard and staple of the gypsy jazz repertoire. Holdsworth’s unabashedly ultra-modern interpretation of the ballad sees him at his most lyrical and it provides an excellent starting point for our foray into his harmonic language. The accompanying harmony of this phrase is simply a ii-V-I progression in G, with the ii chord functioning as a m7b5 and the V incorporating a b9 alteration. This will allow us to see how Holdsworth approaches improvisation in a functional context, and after a simple analysis we can break this phrase down to look at some of the ways we can go about incorporating these types of ideas into our own improvisations.

(You can listen to the lick here starting at 1:58)

We can actually break this phrase down quite nicely into two segments; what he plays on the Am7b5 and then on the D7b9:

On the Am7b5: Traditionally, on a functional m7b5 chord one would use the locrian mode; the seventh mode of the major scale. We know this because the seventh chord in the harmonised major scale is a m7b5 and locrian is the name we give to its accompanying mode, which contains a b2, b3, 4, b5, b6 and b7. However, the first note he plays is a B natural, which gives us a natural 2 instead of a b2. What Holdsworth has done here is something fairly common in jazz improvisation: he has reinterpreted that m7b5 chord as chord vi in C melodic minor, which generates a mode aptly called locrian#2. This is a technique we call modal interchange, and we use it to generate unusual colours and heighten tension. Without getting too sidetracked, although chord seven of the harmonised major scale is a m7b5, so is chord six of any melodic minor scale. Modal interchange is often about disregarding context for the sake of colour, for example using the Lydian on a major seventh chord even if it is functioning as I, not IV.

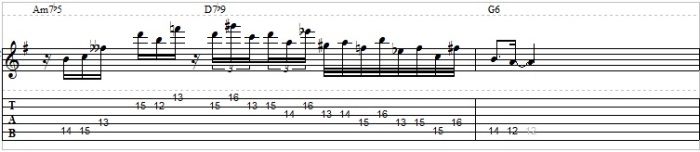

Here is the A locrian#2 mode in tablature and notation:

Even if you don’t quite grasp the theory behind modal interchange (there are a plethora of articles on the subject all over the web) it can just be helpful to know that when you are faced with a m7b5 chord, this mode is another option other than your standard locrian. I like it because it’s slightly brighter due to the natural 2nd and it comes with its own unique colour and mood. Spend some time playing this mode in alternation with locrian over a m7b5 chord and see how it makes you feel. I would argue that the true potential of a mode isn’t unlocked until you hear it in all possible incarnations with regards to intervals and arpeggios, so check the notation and tablature below for those. I did say we were going to deconstruct this stuff, didn’t I?!

As soon as you start to get comfortable with the sound of the mode it will become much easier to use it melodically and musically in your improvisations. Becoming comfortable with how it sounds involves really getting inside it on an aural, intellectual and technical level. It often helps to try and sing these exercises as you play them!

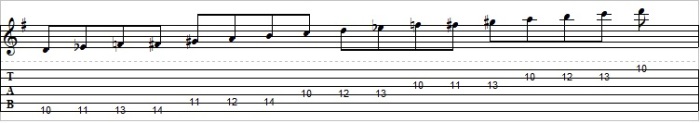

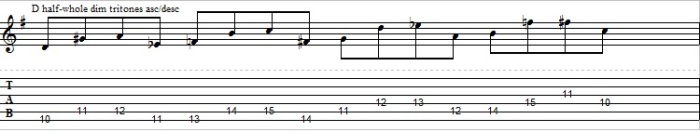

On the D7b9: There are a few things to mention here, but I’ll start with the harmony. Over this altered dominant chord Holdsworth plays a sequential pattern based on the D half-whole diminished scale. This is an eight note scale (sometimes referred to as the octatonic scale) which produces these intervals over the D root: 1, b2, #2, 3, b5, 5, 6, b7. It looks like this:

The four-note pattern he uses from this mode can be broken down into this formula:

- starting note (in this case D), jump a tritone (b5), scale tone below starting note, then back to starting note.

- Repeat this down a fourth from D (so that A becomes your new starting note)

- Repeat this down a major third from A (so that F becomes your new starting note)

- Repeat down a fourth (C is new starting note; only half of the sequence)

Note that you can’t just repeat the same shape down a fourth, down a third et cetera because the third note in the formula is a scale tone below your starting note, which is the note in the scale below the one you’re currently on. This could either be a tone or a semitone due to this scale consisting of alternating half and whole steps. For example, when you start the pattern on A, the scale tone below is Ab, a semitone as opposed to the original sequence in which it was a tone. This just means getting comfortable with the scale and knowing what the scale note below a given note is in relation to the notation provided above. So if your starting note is F, you’ll jump a tritone to B, go the scale tone below F in relation to the D half-whole diminished scale, which is Eb (check above) and then back to F.

This is a really cool pattern for a number of reasons. Firstly, it exploits the fact that you can jump a tritone on any note of the D half-whole diminished scale due to its symmetrical nature. Just realising this can lead to ideas like this:

Furthermore, Holdsworth manages to obscure its obvious formulaic foundations by avoiding grouping them in sets of four. If you notice, the first two groups of four are spread over two sixteenth note triplets and the first two thirty second notes of the next beat. Not only does this stop this pattern sounding overtly ‘patterny’ but it also creates a sense of momentum, tension and release on a rhythmic level as well as harmonic.

We can get a lot of language out of such a small amount of music. I would encourage you to study the half-whole scale in depth as we started to do with locrian #2; learn the scale in all possible intervals as well as uncovering all possible arpeggios on each note (tip: once you’ve worked out all possible arpeggios on the first two notes of the scale, the rest of the scale is sorted).

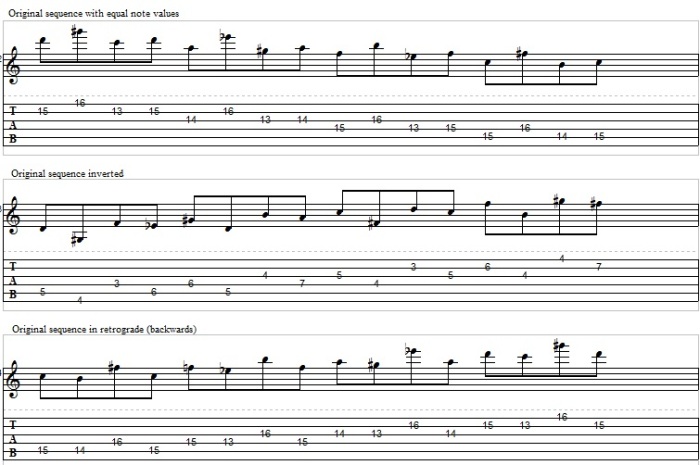

If you want to go beyond merely utilizing the kind of harmony Holdsworth is using here, we can go much further by manipulating the four-note sequence we’ve uncovered. Let’s make all notes in the sequence of equal value and complete the last phrase according to the formula we worked out and see what happens when we apply retrograde or inversion to it:

These techniques have been used for centuries by composers to squeeze the maximum amount of musical material out of one simple idea. As you can see, by simply turning a pattern upside-down or back to front we have generated two new patterns. The final step is to apply both retrograde and inversion to the original pattern. Challenge: try working that one out yourself, by inverting the retrograde pattern.

A Final Word

The main thing I’d like to you get from this lesson is the realization of just how much material you can get out of only a limited amount of music. There are so many different ways you can do this and I have presented only a handful of ways here. It is my hope that this inspires you to get the most out of your transcriptions or studies and allows you to transcend merely learning licks and playing them in your solos verbatim. This way you are coming up with your own material based on a harmonic, melodic or rhythmic idea that stood out to you from a solo or passage of music. Michael Brecker summed up this approach quite nicely: ‘I listen to things and then I learn them or I hear them enough and they get into my psyche and then I distort the hell out of them.’ By taking something from a passage of music and running with it as far as possible you ending up arriving at totally new ideas so far-removed from the original you’d never know. This could be simply analyzing the harmony and exploring the modes used as we did for the Am7b5 chord, or taking a phrase and flipping it upside-down or back-to-front as we did for the D7b9. It could be far less specific and more conceptual; looking at the latter phrase as a four-note-descending-diminished-intervallic-thingy and coming up with your own loosely based on it or not based on it at all.

I hope this has been helpful and informative. If you have any questions on anything at all, drop me an email at aelliottwilliams@gmail.com. Next up we’ll be analyzing some passages from Arnold Schoenberg’s music and working on ways of incorporating them into our improvisations.

Happy Practicing!

Alun Elliott-Williams